A Brief History of Credit Transactions

“Cash is king, ” is a sentiment that has long denoted the importance of real physical currency. It’s reliable, consumers and merchants alike put their faith in it, and for good reason. Through history, real physical currency has been the gold standard for person to person, and person to business transactions. Of course, as time went on it became completely impractical to carry around large sums of cash for everyday purchases, and checks, while convenient for the consumer, are slow and present some risk to the business owner.

In the 1950’s and 60’s, the first “charge cards” were introduced, they allowed consumers to pay for leisurely activities and commodities like entertainment and dining out. To authorize these card transactions, merchants needed to check the card number against a large book of card numbers to ensure the card was valid, then the merchant had to send physical paper drafts to the institution that issued the card, who would debit the customer’s account upon receiving them. While these early cards weren’t particularly mainstream, businesses would typically still pass along a “surcharge” to account for the fees that the financial institutions would charge the merchants for using the service.

However, the practice raised concerns when it came to consumer protection and transparency of lending rates and product prices. The lack of government regulation only raised the concerns of consumers, card lenders, and government officials alike. This led to a temporary ban in the 1970s, which was later allowed to expire in the early 80s. Since then, credit surcharging has had a “rough go of it” when it comes to being banned or heavily regulated at the state level, with private institutions also placing restrictions on the percent surcharge merchants are allowed to pass on to consumers.

Of course, this doesn’t feel entirely right for merchants. While it’s completely fair that there are concerns around the transparency of surcharges, are merchants just supposed to take the hit? That might be fine for a large institution like Walmart or McDonalds, but small businesses need to make every penny count, or they could be putting their livelihoods at risk. In 2024, only 16% of transaction payments were made in cash, with that number projected to drop down just 6% by 2030. In 2002, it was considered ridiculous when the first ever McDonald’s began accepting credit cards at their location, leaving the average consumer confused as to why someone would ever use a credit card for such a small purchase. But now, over twenty years later, roughly 40% of businesses in the Unites States have gone completely cashless.

The Fall of Cash Payments

One reason for the increased adoption of credit cards by consumers is that they just keep getting more and more convenient. Credit cards have come a long way since their inception, what was originally a piece of cardboard is now a surprisingly advanced piece of plastic. The addition of the magnetic stripe, the even more secure chip, and most recently the EMF reader enabling “tap to pay” behavior? Who wouldn’t want to use something like that? Why go through the hassle of getting out your cash, waiting for your change, and then getting back some assortment of coins that you’re just going to lose in your car anyways, when you can just wave your magic piece of plastic over the payment system and be done with it?

Another recent contributing factor to the use of credit cards over traditional cash payments was the COVID-19 pandemic. While the world altering and enduring event spurred far greater tragedies than decreasing the rate at which people paid with cash, that was a bi-product of the global event. Not only did many businesses stop taking cash payments at this time, to reduce the risk of disease transmission, but online shopping became far more prevalent, with a global increase in sales of 22% in 2020 alone. While that may not sound huge, pre-COVID-19 projections predicted growth at only 9-12%.

The fall of the great “cash empire” as a preferred payment method seems inevitable, as consumers are consistently deterred from using cash, whether by technological convenience or world events, while the merchants have to deal with the financial consequences.

The Burden of Credit on Small Businesses

For large corporations, credit card processing fees are simply another line item on a long ledger of operating costs. An annoyance, perhaps, but not a threat. These organizations have entire legal teams to negotiate with payment processors and can afford to absorb or offset fees in a number of ways. But for small business owners, the story is very different. A 3% processing fee on a $10 transaction might seem small, but across hundreds or thousands of sales per month, that cost adds up. In lower-margin industries like food service or retail, those fees can eat directly into the owner’s income.

And it’s not just the fees themselves, it’s the uncertainty. Different cards carry different fees. A customer paying with a standard debit card might cost a business 1.5%, while a premium rewards card could cost more than 3%. Merchants have no control over which card the customer uses, but are still responsible for covering that fluctuating fee. The irony is that those premium cards are usually issued to higher-income consumers who are being incentivized with cashback or points programs, rewards that are ultimately paid for by the businesses they frequent.

Small businesses have been calling for change for years. Some have even tried going cash-only as a protest or cost-saving measure, but this comes with its own consequences: fewer customers, slower service, and in some cases, public backlash. In today’s economy, refusing to accept cards can feel like commercial suicide. Most consumers simply expect to use their preferred payment method, and businesses are expected to comply.

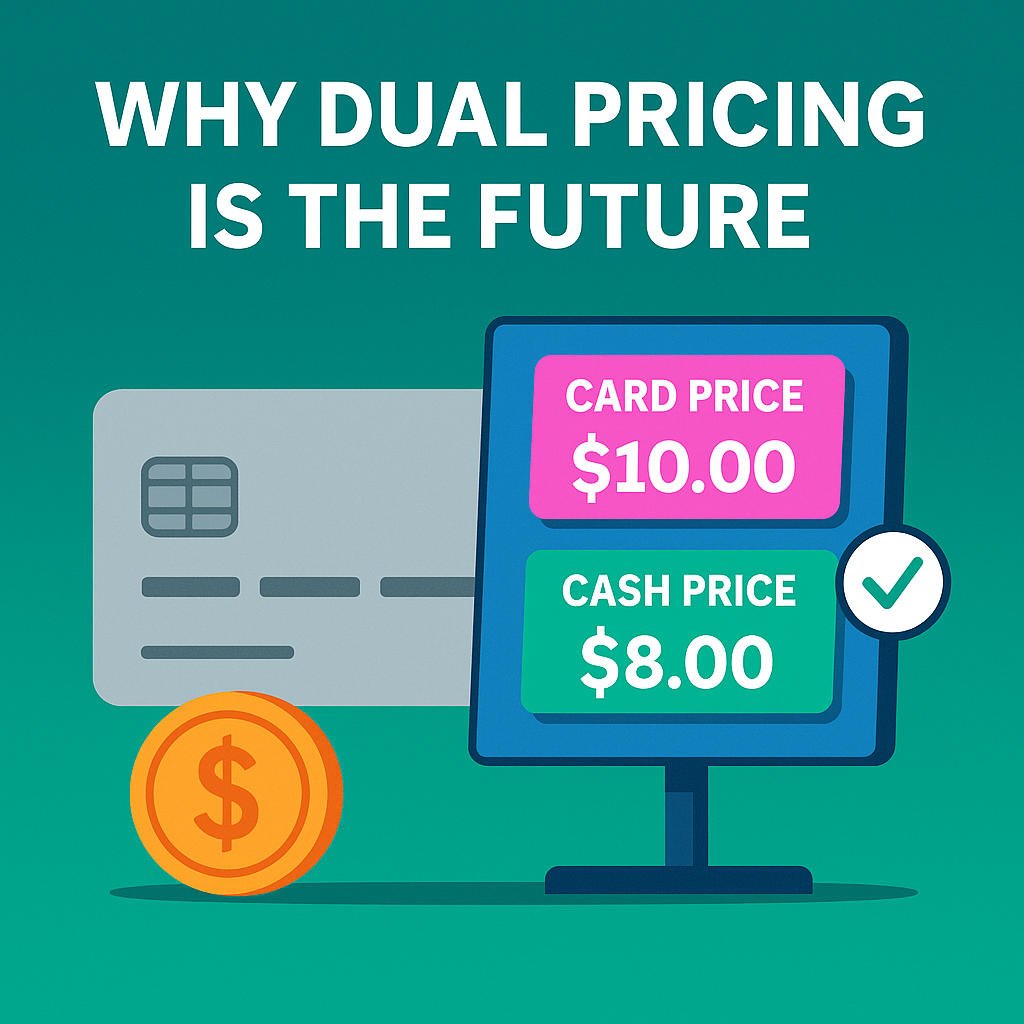

Dual Pricing, the Revitalizer of Cash Businesses

So, what is the solution to this decades-long pricing conflict? How can we encourage consumers to pay in cash, and mitigate the financial burden of card payments. That’s where dual pricing comes in. Dual pricing is the practice of giving the consumer two prices at checkout, one being the unaltered price of goods, the other being the price of goods with an additional percentage tacked on, representing the cash and credit pricing for the transaction, respectively.

But, what exactly is the difference between a credit surcharge, and dual pricing? For starters, dual pricing is a nationwide accepted practice, whereas surcharging is still either not permitted or heavily regulated in some states. The purpose behind the two practices is also completely different. Surcharging is, at its core, meant to offset the cost of fees for a merchant, however this fee can be seen as opaque and is only ever applied to credit transactions. Dual pricing does away with the issue of transparency, in fact, dual pricing outright tells you what the difference in cost would be between cash and card. This is because dual pricing is meant to encourage consumers to use the less costly transaction medium, protecting their right to make that decision for themselves, while reducing the burden of transaction fees on the merchant.

In a world where convenience and speed increasingly shape consumer behavior, the decline of cash is not just a trend, it’s the way commerce seems to be headed. While digital payments and credit cards have undeniably enhanced the ease of transactions for consumers, they’ve also introduced significant financial strain on the businesses that rely on them. For small business owners especially, every transaction fee can chip away at already thin margins, threatening long-term sustainability.

The solution isn’t to resist progress or vilify consumers for choosing what’s convenient, it’s to adapt in a way that is transparent, fair, and sustainable. Dual pricing offers exactly that. By providing customers with clear choices and empowering them to understand the cost differences between cash and card, this approach promotes informed decision-making while protecting merchants from the silent burden of rising processing fees. Unlike surcharges, which often feel hidden or punitive, dual pricing is upfront, legal across the country, and designed to respect the needs of both buyers and sellers.

As cash usage continues to dwindle and digital transactions dominate the marketplace, the need for equitable solutions will only grow. Dual pricing isn’t a gimmick or a temporary fix, it’s a practical, consumer-conscious strategy for navigating a financial system that increasingly favors convenience over cost. If we want to ensure a fairer, more balanced economy, an economy that supports both innovation and small business resilience, then embracing transparent models like dual pricing may be one of the most important steps we can take.